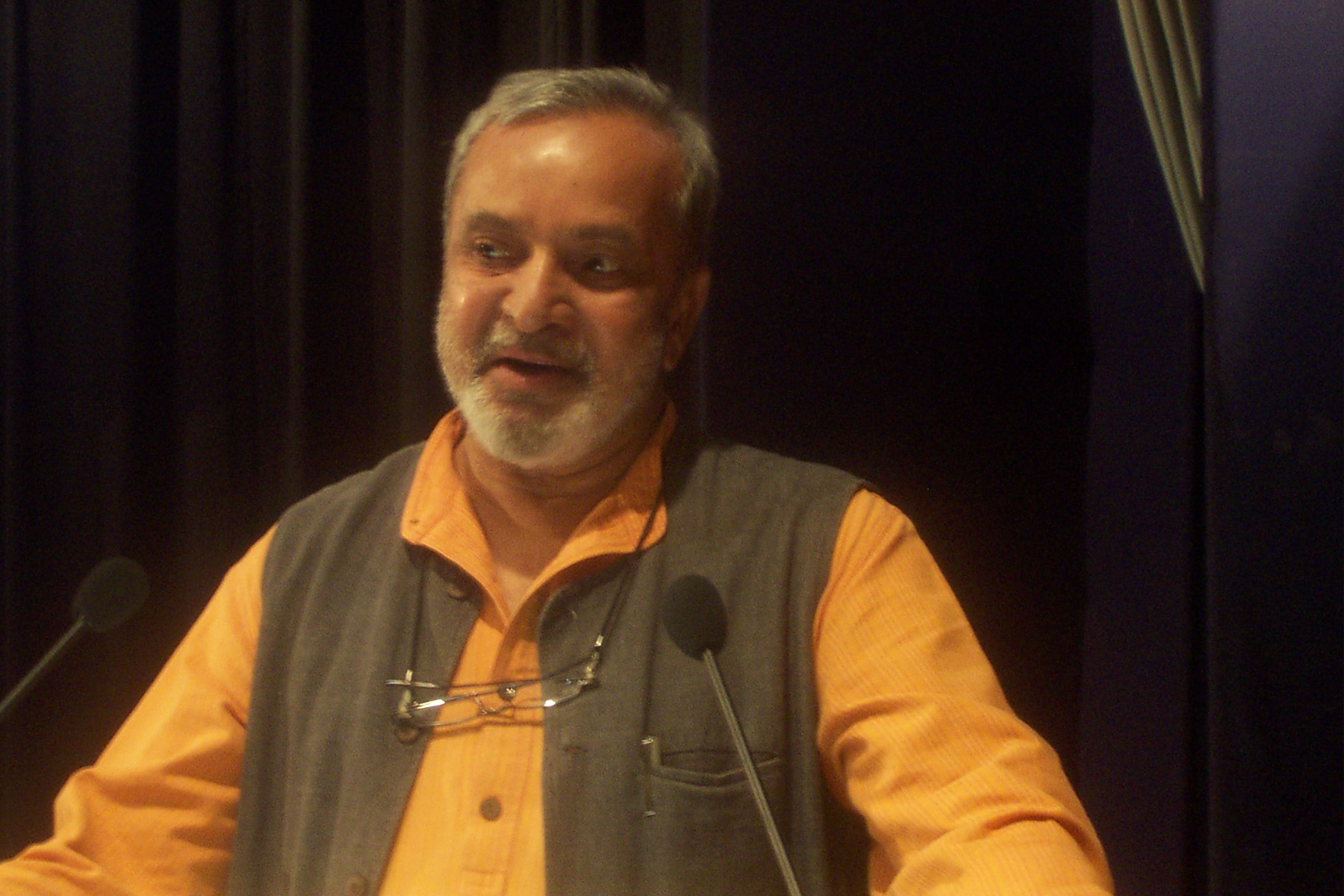

courtesy:seminar

The problem

THE Kannada writer, U.R.

Ananthamurthy, died on 22 August 2014. People mourned him as a great public

intellectual, a man whose quarrels, writings and conversations created a

commons of ideas for democracy. Ideas need sustenance, a language, a set of

metaphors, the enzyme of gossip to sustain them, which Ananthamurthy with his

feats of storytelling provided in abundant measure. This issue of Seminar is an attempt to assess the man, to provide some

sense of the world he created. How does one assess a life which permeates an

entire culture, quietly providing the songlines of debate?

I am reminded of a

wonderful friend of mine, an almost impish character, who was reading a tribute

to a great writer. He read it quietly, and then read it again. I was intrigued

by his silence and asked him what he thought of the piece. He said, ‘Droppings.

Name droppings. Word droppings. There is a connection between bloated words and

bloated egos. I wish one had talked about the man, what he felt, what he dreamt

of, who he loved, what mistakes he made, what regrets he had – not this

immaculate pastiche of politically correct phrases. If criticism becomes

correct, it will be the death of conversation.’ He stopped: ‘I love an India

where we build icons to iconoclasts.’ He smiled and then said: ‘The irony would

appeal to URA. At least here irony, metonymy, paradox, every trope he loved was

present. I remember a group of people celebrated his death with firecrackers. I

can see him, part of the crowd, watching the whole scene with quizzical

interest.’

In a way the man was

crafted like a novel where every sentence was a nuance, every line a strand

from memory. Memory was the commons from which his ideas emerged. Yet, he added

to memory the art of conversation. He was a remarkable listener and he crafted friendship

like his stories. He had a huge following but never considered it as a mass, a

collections of fans. Each individual, housewife, critic, bureaucrat, school

kid, taxi driver felt a personal link to him, a particular claim, a memory, a

special moment of remembrance. He was a ganglion of all who knew him. Each

story was concrete, personal and particular.

In that he was different

from almost any intellectual I knew. For example, some are obsessed with work

but they collect nuggets of information, not people. Others are admired for

what

they write but one does

not quite want to meet them. URA moved like a happy bee pollinating a

community. He thrived on the little moments, morsels enjoyed in anonymity. He

had an openness and trust which allowed people

to quarrel with him and

yet he hugged them in welcome the next day. One could differ with him and yet

had to love the man. There was something so endearing about him. He was a guru

but had neither gurukul nor gharana. He loved the openness

of café intellectuals which he grew on, the give and take of celebrating ideas.

He thrived on the yeast of conversation and he realized politics without the

art of difference is no longer politics.

He was a teacher, an

exemplar. He could be firm. I remember at one Ninasam session, in Heggodu, my

attention was wandering. I was tired after a long lecture, a bit irritated with

the questions. He reprimanded me quietly. ‘Listen, learn and respond, you owe

it to them.’ He was an immaculate listener. He could take any question, even a

dull one and turn it into a little work of art to which one wanted to

immediately respond. In a culture where intellectuals are content to score

points, he connected them into a picture. Yet, he could stand alone in an

intellectual fray, admitting that people were angry with him. He was passionate

about his ideas and their demands. Often he would be indifferent to readers

when experimenting with an idea. ‘Then I have to write myself out.’ He was

supple about himself.

URA was born on 21

December 1932 in the kingdom of Mysore, lived in a forest and as a brahmin boy

lived out the logic of pollution at its most intricate level. He lived in a

world where everything was sacred. A forest in childhood is a sensorium of

fears, sounds, smells, where each night brings its own trail of anxiety. Fear

needs to be domesticated by summoning the Gods, by invoking prayer, and without

these tremors of fear, no story can be born, no myth relived. A forest also

gives a sense of the sacred, providing a train of taboos, of worlds that one

should not touch. Violation of taboos brings the Gods down on you and the first

fights of rationalism and its protests are acts of sacrilege, of piddling in

defiance on temple stones. Oddly, even protest has its rituals in a brahminic

world, where rituals mark all things. Between taboo, ritual and the sacred, a

brahminic world creates its weave, implicating everyone mercilessly in it. Even

critics and rebels are but different kinds of storytellers showing how deeply

society has encoded them. These childhood years marked him as a sociologist of

ritual, where even protest as drama enacts a variant of society.

Beyond ritual and its

fascinations, the play of ideas was critical to URA. Maybe every act, every

debate, is a re-enactment of the conversations in a college canteen, where an

idea is always a commons, where each debate ploughs a domain till it becomes

richer. A few exemplary teachers and a hunger for ideas and friendship can

create an intellectual community. That richness of memory becomes the creation

myth of every later conversation. Conversation becomes a compost heap which

perpetually renews itself. The ascetic and the aesthetic combine here to create

a style which is unforgettable. One recites the name of every writer and

journalist as if one is savouring each creative act, each a puffball of

memories, works, debates. Kuvempu. Govindaswamy, Ramanujan, Subbanna, Karnad,

Chitre, Kasaravalli, Nagaraj and, as the years go on, a younger generation

feasting on a past, proud of a language that has given them a world in common.

It was a world where swadeshi and swaraj combined unconsciously and effortlessly.

Swadeshi was the local school

teaching vernacular. Yet swadeshi was never parochial, never confined to the

local. Locality was about rootedness, an embeddedness, of languages, soil and

cuisine which smelt of local in all its variants, the sensuality of the

everyday. Through translation, through interpretation, swadeshi became swaraj not only through the academic cycles of

storytelling, but through interpretations, re-reading, where every story

becomes a cosmos of reinterpretations. Such worlds revere the storyteller. URA

was a trickster who could put Galileo and Gandhi, Milton and Tagore, Jatra, Yakshagana and Kabuki together. Retelling is important

because stories have to be retold, to be renewed. Retelling is an act of

trusteeship and the storyteller an indispensable trustee of society. It reminds

one of Mario Vargas Llosa’s novel, The Storyteller, where a tribe survives as long as their story is told again and

again.

This issue then is a

tribute to a storyteller, who was a public intellectual. It is an attempt to

analyze his ideas, his life, his milieu, as tribute and as critique. It asks

the following questions. What does the nature of language mean to a writer?

What does it mean to be a revolutionary in a ritualistic world? How does one

carry out a conversation of ideas which affects every citizen? How does one

compost childhood into the imagination? What is translation? How does one make

democracy more creative and the political more inventive? What is the role of

memory and invention in our culture? What is the relation between politics and

the novel? What does writing as creativity tell us about other arts? Can

listening to music tell you about writing?

This is not a journal of

techniques of a how to do it book. It is a quarrel, a set of conversations with

an extraordinary man. One can see him in the mind’s eye consuming it like

another story, responding like another Scheherazade with another ‘Once there

was…’

SHIV

VISVANATHAN

Rice and ragi: remembering URA

SHELDON POLLOCK

THERE is a time and

place for impersonal scholarship to assess the creative work of U. R.

Ananthamurthy, and to make sense of what it has meant and is likely to mean to

Indian literature in the future. There is also a time and place for personal

acquaintances to reflect on their friendship, and to make sense of what it has

meant to their own lives. The recentness of URA’s death and my long attachment

to him prompt me now to reflection rather than assessment. And while I want to

reminisce for the record – I know this is what URA would have appreciated –

what I see emerging from these reminiscences are two larger, even defining

features of his life and work around which I can organize my thoughts: his

relationship with India’s language order and his relationship with the order of

the world.

The face of (a very

young) Girish Karnad was staring from the screen at the end of the film version

of Samskara when I walked into a room at the University of Iowa in the spring

of 1975, as a twenty-seven year-old professor just beginning my career, and met

URA for the first time. I was coming to the university to teach Sanskrit but also

to succeed him as instructor in Asian literary humanities. Something in that

configuration of concerns – literature, Asia, and Sanskrit – and in fact in a

particular sub-configuration of that configuration, was to lie at the core of

our friendship for the next forty years. For it was a relationship that lived

on and sustained itself through literature in general, Indian literature in

particular, and the peculiar bond that exists between big and powerful

languages like Sanskrit or English and smaller and more embattled languages

like the one to which URA devoted himself heart and soul, Kannada.

I guess you could say

that the single most consequential act in URA’s writerly life was the choice to

take the side of the embattled – as he would do in all the rest of his life –

and to use Kannada for his literary writing. Others in this issue of Seminar will no doubt have something to say about URA’s postgraduate work

in Birmingham UK in the late 1950s: about the remarkable circle of friends and

mentors who surrounded him there (Richard Hogarth, Malcolm Bradbury, David

Lodge, Stuart Hall); the historic intellectual moment he participated in that

saw the dawning of cultural studies; the dissertation he wrote on the British

Marxist novelist Edward Upward (who, it is astonishing to learn, died only five

years ago, at the age of 105); and URA’s immersion in English literature in

general, for it was the field to which he would, academically, be affiliated

through his active teaching career. What for me is most significant about this

postgraduate experience, however, is the choice he made then to reject English in

favour of Kannada.

Anyone who has ever read the utterly charming,

seemingly artless English that URA wrote in his scholarly essays understands at

once that the act of abandoning the language in his creative work was not a

necessity but a choice. It was one that affiliated him with a deep history of

choices of which he was fully aware, just as he was fully aware of the politics

such a choice entailed. All these issues – political, historical, aesthetic,

and existential – that were associated with the decision to use the particular

literary language he did use marked as much as, or even more than anything

else, URA’s identity as a writer and – to move from great things to small –

marked the intellectual impact he exercised on one particular friend.

I saw these forces

vividly at work when at my invitation (and with the support of a Fulbright

fellowship) URA returned to Iowa City to spend the academic year 1986-1987.

Soon after he arrived, we decided to sit down together and translate one of his

first short stories, ‘Prakriti’.1 As we worked our way

through the piece word by word – despite the fact that my Kannada then was

rudimentary (as it has once again become) – I experienced at the most intimate

level both the large structural relationship between Kannada and Sanskrit but

also URA’s very careful modulation and balancing between the two codes. I

witnessed the powerful affective hold Kannada held for him, and the joy with

which he explained its nuances to an (almost) outsider. The translation itself

was to have appeared in one or another collections, yet never did; it is seeing

the light of day, finally, in this issue of Seminar.

‘Prakriti’ is, for me at

least, what Sanskrit would call an anvartha nama,

a word that perfectly embodies its referent, since the experience of

translating it lingers as a foundational one in my memory and life. Not only would

Kannada become a scholarly interest of mine from that point on, but a larger

research project began to take shape in my mind, on what I would come to call

the problem of cosmopolitan and vernacular in history. However vague at first,

the project would come to obsess me for the next decade and a half, and it was

one on which URA, in his own way as a contemporary writer grappling with the

problem, would be an active interlocutor.

When I say URA ‘chose’ to write in Kannada, I

want to make clear, if it is not already, that both the possibility of literary

language choice and the obligation to choose truly exist for many contemporary

postcolonial writers, especially Indian writers, in a way and with a degree of

compulsion (and anxiety) that they do not for others, the so-called

metropolitan writers. And in India, as elsewhere if less intensely, this choice

is by no means postcolonial; instead, the literary world had long been

structured by a complex ‘language order’ (a concept I borrow from Andrew

Ollett). For two thousand years, being a writer in India had always entailed

the necessity of choosing and, by that choice, affiliating oneself with one or

another competing – and sometimes conflicting – aesthetic, social and political

vision.

Ananthamurthy was fully aware of all this, since

he was deeply interested in the deep past, if less expertly knowledgeable about

it than he would have wished. (He could not help me with Old Kannada himself,

but he had the foresight to direct me to the great scholar T. V. Venkatachala

Sastry of Mysore.) Indeed, it was from discussions with him that my own long

gestating ideas took on greater nuance and cultural-political urgency. I began

to see that, as in so other many instances of deep cultural theory, classical

India had a great deal to teach the rest of the world: it had actual categories

for cultural phenomena that were common elsewhere but completely unnamed, and

hence, unknown. In this case the terms are marga and desi, languages of the ‘Great Way’ and those ‘of Place’, which, for

reasons I have tried elsewhere to clarify, I would eventually decide to

translate as ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘vernacular’.

I began to see that

these were not only literary-critical terms but broadly cultural, informing

traditional understandings of diversity in everything from dance to music to

food. And they were, or could arguably be held as, broadly political, since

they were associated with varying forms of (respectively) transregional and

regional power. According to the analysis of Indian culture-power I began to

develop in the 1990s, Sanskrit ruled as the language of empire for a millennium

or more starting around the beginning of the Common Era, and would eventually

be replaced, some ten centuries later, by other, more circumscribed formations

that I called vernacular polities, in part because they prioritized regional

language for the expression of political power.

Of course, in many ways

a vernacular-political language such as Kannada could itself take on a certain

cosmopolitan character, both in its interaction with Sanskrit and in its

domineering relationship with languages of smaller worlds such as Kodagu or

Konkani or Havyaka (in which a movie version of the ‘Prakriti’ story has,

somewhat ironically, just been produced), or indeed, URA’s own language, which

was basically Tulu.2

This peculiar kind of synthesis that India found

generally so easy to effect – in contrast to more assimilative formations,

whether ancient empires such as Rome or modern nation-states such as England or

France – offered a kind of template that URA readily transferred to

contemporary politics. An example he was fond of citing was the election in

December 1984, which saw the ‘marga’ candidate Rajiv Gandhi elected from the

all-India Congress Party as prime minister of India, and the ‘desi’ candidate

Ramakrishna Hegde from the locally-inflected Janata Party as Karnataka chief

minister. He could similarly think of sociological categories in the same

terms: thus, class was ‘marga’ whereas caste was ‘desi’.

With URA’s help, I began to see that Kannada

itself was conspicuous in world literary history for its richly layered,

long-term arbitration of these different valences, not uniquely so – given, in

India, the somewhat later history of Telugu, among other examples, or, in

Europe, the considerably later history of Italian, again among others – but

conspicuously so. With the characteristically earthy wit of the Shimoga

villager he was always proud to be, he gave expression to this categorical

diversity through the metaphor of rice versus ragi, the ubiquitous white refined food of the urban elites (and

high-caste ritual specialists) and the very local hearty millet of the rural

poor. This was a conceit he long cherished: he mentioned it to me in

conversation first around 1986; so far as I can tell it first appeared in print

in an introductory essay to the photo album Karnataka: Impressions, 1989, and more recently in these pages in a 2010 interview with

Chandan Gowda (it derives ultimately from the 17th century Kannada poet

Kanakadasa).

The extension that he

could have made but did not, or did not wish to, make was that rural people do

not actually want to eat ragi, however wholesome they know it to be. They

prefer to eat the white rice that will weaken them… and to learn the English

that will weaken, or even kill, Kannada. Indeed, what pained URA as much as

anything in the world was to observe the long arc of the nourishing vernacular

tending toward decline under the power of white-rice English.

All these ideas – about

the writer’s commitment to Kannada and about the great Kannada poets and

thinkers past and present – manifested themselves not just in our purely

intellectual exchanges but in the relationships that URA made possible for me.

It is to him that I owe my friendship with the great Dalit poet Devanur

Mahadeva and the inimitable Girish Karnad, my acquaintanceship with the

playwright Chandrashekhar Kambar and the literary historian and critic

Kirtinatha Kurtakoti, among countless others. Even my interactions with my dear

colleague A.K. Ramanujan took on a special aura because of URA (Raman actually

edited the draft translation of ‘Prakriti’ in 1989).

But foremost among all

these new friends was D.R. Nagaraj, who before his tragic death in 1998 was

about to accept a professorial appointment at the University of Chicago (I had

thought of him as the successor – a man from the world of ragi rather than the

world of rice – for Raman, who died in 1993). It was his support for DR over

many years, his affection for and loyalty to him, his engagement with his

ideas, his shared temperament, that embodies for me everything that was so

wonderful about URA: passion for literature; genuine admiration for learning

with real depth; profound connection with Kannada as both an old and new

literary language; lifelong commitment to the battle against social inequality;

and last but hardly least and hardly negligible, magnetic charm and joyful

playfulness.

Ananthamurthy’s commitment to Kannada was

inseparable from his love of Karnataka. A good deal of his prose writing was

about the land and the people and the ways of life on that wonderful spot of

earth, object of such remarkable emotional attachment from as early as the 9th

century. ‘Between the Kaveri and the Godavari rivers’, so the great Kannada

treatise on poetry and polity, ‘The Way of the King of Poets’ (Kavirajamarga),

puts it ‘is that culture-land (nadu) in Kannada, a well known

people-place (janapada), an illustrious, outstanding political realm

within the circle of the earth.’

From an early date

Kannadigas had known to situate this special place in the wider world. Entirely

typical is a 12th century inscription from northwest Karnataka from a tiny

Brahman settlement: ‘In Jambudvipa, best of all continents, lies Bharatavarsha,

most exalted of regions… In it is found Belvala, native soil of the multitude

of all tribes… In it lies the Nareyangal Twelve, and therein is found the

celebrated agrahara named Ittagi.’ (In a way I cannot quite

articulate, this telescoping in – bringing the big world into the little –

seems to me different from and preferable to that of the telescoping out –

projecting the little world into the big – found in say Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist: ‘Stephen Dedalus, Class of Elements, Clongowes

Wood College, Sallins, County Kildare, Ireland, Europe, The World, The

Universe.’)

This peculiar orientation is a perfect

geographical counterpart to the ‘cosmopolitan vernacularism’ of Kannada writers

and thinkers, both ancient and modern, where the two great tendencies in

culture and power could each find its proper place. And it is entirely

evocative of URA’s own way of being: he lived his life and made his art in such

a way that the whole world was meant to be contained in the language and themes

of the ‘land of the black earth.’

I was fortunate to have

been able to travel through much of the state with URA, typically on the high

hard seat of an Ambassador on loan to him in connection with this or that

administrative posting. I remember the glorious days we spent in Kodagu amidst

the coffee fields, or in the western ghats en route to the wildlife preserve in

Thekkady, where after several early risings we succeed in sighting not much

more than some elephant turd and Lord Rama’s three-striped squirrel. But then,

seeing animals was not really the point of the trip.

In the spring of 1987, URA asked me to sit and

talk with him about an invitation he had just received from the then chief

minister of Kerala to become vice chancellor of Mahatma Gandhi University, a

new postgraduate institution in Kottayam. Or perhaps the invitation was

mediated by Ramakrishna Hegde, the chief minister of Karnataka, for part of the

issue in URA’s decision whether to accept or refuse was the worry of

disappointing political associates in his home state. It was clear to me at the

time, and even more to URA himself, that accepting such a position for so long

– I think it was at least a two-year appointment – would seriously interrupt

his literary career.

And indeed, most readers

would probably agree that his output from the 1990s on did not reach the

heights of commitment and passion and artistry of the earlier works. But URA’s

decision to accept was based, aside from local political concerns, on another

core aspect of his character: his commitment to social and economic justice,

and to equal intellectual opportunity. To help build a new university in a

progressive state to serve the needs of common people spoke too directly to

many of his concerns to ignore. Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is by

telling a few Kottayam stories.

When URA got to the

Kerala university he needed someone to help with the cooking. An acquaintance

of his, a political activist and member of the Irava community, had recently

died, leaving his family destitute. URA immediately hired his late friend’s

sixteen-year-old son as cook. It was inconsequential to him that the boy could

hardly find his way around a kitchen (he once succeeded in turning magnificent

fresh fish I had bought on a backwater boat ride into shoe leather). It was

entirely typical of URA that he preferred to eat poorly for two years, as he

wound up doing, rather than forego the chance to help a person in need.

I was not present during

the drive in 1989 (one not started by URA but vigorously promoted by him) to

make Kottayam the first city in India to achieve one-hundred per cent literacy;

among other things, URA arranged for reading glasses for aged illiterates eager

to be able, finally, to learn to read (the Silver Jubilee of this event was

celebrated in Kottayam this past June 25).

Another visit of mine to Kottayam later in that

same summer coincided with the tragic events of Tiananmen Square. I accompanied

URA to a tense meeting of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in central

Kerala (I forget now where; it might have been Alleppey). While the last

Stalinists in the world were busy purging any member who denounced the state

atrocity, URA stood up and gave an impassioned speech in defence of the

slaughtered students, entirely secure in the conviction that he must speak

regardless of the mood of the gathering.

URA ran his vice

chancellorship of MGU in the same way, receiving on a daily basis streams of

what seemed petitioners or even suppliants, whether from the staff, the

students, or, most typically, a union representative, who came seeking URA’s

intercession in this or that cause or with this or that person abusing their

authority. At the same time the vice chancellor was encouraging the most

intense discussions around freedom and dignity in the university’s School of

Social Theory. There was no theory-practice contradiction in URA.

It had been much the

same during his Fulbright year in Iowa City. URA had gathered around him a

group of brilliant young Indian students, all of them at once artistically

creative and politically radical, just like himself: Suketu Mehta, Kabir

Mohanty and Sharmistha Mohanty, V. Geetha, the late Bala Kailasam, among

others. His quest for social transformation was infectious. At the same time,

he travelled widely in the US, most memorably to the deep South, where he

talked to African-American youngsters about social change, non-violence, and

the ties that bound him and them together. URA believed that honest men and

women committed to real revolution must put their time and energy where their

mouths are, and unlike most of us, he did so constantly.

Others in this issue of

Seminar will, I hope, discuss more deeply than I am able to do URA’s actual

political life in Karnataka, such as his relationship to the old Socialist

Party and Janata Party of Karnataka, his unwavering resistance to the

Emergency, or his lifelong admiration for the (largely if unjustly forgotten)

political theorist and anticolonial revolutionary Ram Manohar Lohia, Ananthu’s

admiration no doubt in part stemming from Lohia’s own sense of priority of the

anthropological desi – caste – over the sociological marga – class.

Progressive politics was

baked into URA’s character, and it is no surprise he preserved that spirit to

the very end of his life, as his profound concern at the 2014 election testifies.

His death is a source not only of deep sorrow to his friends but of worry to

anyone who cares about the orders he cared about, the order of language and the

order of the world, and understands, as URA understood so well, how deeply the

two are connected.

Footnotes:

1. I feel sure he told

me it was his first, but the original appeared only in his second collection, Prashne, in 1963. URA apparently found unsatisfactory the translation by

Sumatindra Nadig (in Sixty Years of Kannada

Short Story, ed. L.S. Seshagiri

Rao, Kannada Sahitya Parishad, 1978; he mentioned another, earlier and very bad

version that cannot now be traced). Narayan Hegde, the translator of URA’s

short stories, published a Hindi version in Ajkal in 1963. (I thank him

for this bibliographical information.)

2. 2013; directed by

Panchakshari, produced by Art Films, Bangalore.

My Amarcord

SHARATH ANANTHAMURTHY

MY appa was not an intimidating father. In my memory, he is ever present,

immersed in the affairs of the world or in his writing, yet constantly with me,

a large, warm and comforting presence who could change my entire perspective on

an issue with just one word or an observation. My earliest memories, from the

days spent in Birmingham, are of creating from rearranged sofas and chairs

covered by bedspreads, darkened ‘tents’ where he would crawl in with me in

between his thesis writing lying in wait for the tiger. We would both be very

quiet and he would ask me to lie very still and keep a watch for the prowling

beast in the vicinity. The game would go on for a while and after a successful

capture (or hunt, for I was fascinated by guns and cowboys at the time) he’d go

back to his thesis writing.

On other days it would

be memory games, where he would make me listen with attention to a sequence of

words, phrases and as I got better at recalling, an entire short poem. He would

tell others about how I managed to listen to things and recall the entire piece

at one go. I can’t remember now if this feat was as remarkable as he made it

out to be, but I enjoyed seeing him say this to others beaming with pride, and

did not feel like spoiling this.

Still too young for

kindergarten, I would devise rituals at home to try and prevent him from going

to the university. One of the rituals was that he would have to say goodbye

several times while I hid behind the furniture and finally, as I let him go

reluctantly, he would have to turn back once near the gate and wave me a

goodbye as I watched him from the window above. I could not understand what

this ‘thesis writing’ was all about. From watching him typing away with one

finger on a typewriter, or making note cards, amidst the din of the Indian home

my mother had put together, I’d sometimes declare to Martin Green, the English

writer and critic who used to visit often, that I was busy ‘writing my thesis’.

We lived in a ‘poorer

England’ and appa had to support the family with a meagre scholarship. Our

small flat was made a home with furniture that was rented, and a TV set that

was recovered from an abandoned pile of things by the roadside. Appa, who had

an acumen for radio and TV repair, had fixed the broken TV painstakingly

figuring out the problem with the connections of the valve and tubes device.

The spool tape recorder would spew out, with the tone getting warmer as the

valves of the device heated up, old Hindi songs, and the Beatles, who had filled

the airwaves by then. He loved the Beatles and in later years I remember him

often talk about how they created both new sounds and a new consciousness in

the West.

I was nearly four when

we moved back to Mysore, with my sister Anu, an addition that happened in

England, and spoke only ‘British English’. Very few in Mysore could understand

me, but all my relatives, I remember, marvelled at the ‘young Englishman’. The

only friends I seemed to be making was with the girls who spoke to me in

English and who went to the ‘best school in Mysore’ which, as someone had

advised appa, was a convent run school. He had returned determined to

re-establish his connections with the Kannada cultural and literary world, and

it dismayed him that Kannada was yet to become my mother tongue. It was then

that I joined a school in Saraswathipuram, a middle class neighbourhood. Soon

after joining school I began to ask appa the meaning of some of the choicest

expletives in Kannada. This had probably reassured him as he had a big smile on

his face. A few fisticuffs later, bruised and crying, I had picked up Kannada

from the local boys in the neighbourhood school. We lived in a house that was

part of a row of houses opposite a large empty field where big ponds formed

each time it rained and filled the night with the sounds of croaking frogs and

chirping crickets.

I remember that almost for a year, on at least two

Sundays every month, Shivaram Karanth, the distinguished Kannada writer and

activist, would show up early in the morning, his big white ambassador parked

somewhere in the field opposite, his driver Anand patiently waiting with a

smile as I ran out and jumped into his car to spend a long hour or two chatting

with him. As I ran out, Karanth would surprise me, posing a funny question, or

sometimes just ‘meow’ like a cat! Appa, a young lecturer then at the Regional

College in Mysore, regularly had diverse visitors at home, ranging from his

English department colleagues, who were quite bohemian in their ways in an

otherwise conservative Mysore, to the doting young students mostly from Kerala

and Karnataka, who needed advice on their love affairs or petty quarrels.

Then there were the

Dalit activists and even the rationalists, who saw in the writer of Samskara a torchbearer in their fight against the evils of caste and

associated superstitious practices. Devanuru Mahadeva, a young man just out of

his teens, was a regular visitor. I remember appa talk to his writer friends

about the genius of Odalala, Devanuru’s novella that had just come out. I was

quickly losing whatever ‘English touch’ I had acquired, although with some

regret for this quality had given me much mileage in Mysore. As for appa, I

could notice a conscious and deliberate move towards a more desiKannada culture, in the causes he espoused in support of Kannada,

causing much discomfort in some of the more English-oriented department

colleagues and other cosmopolitans of Mysore who otherwise admired him.

My school days were a heady mix of fantasies

about the girls around in school and the neighbourhood and, at home, the

animated conversations that I watched or listened to in between my cowboy or

police-robber games that consisted mostly of running through the rooms of our

little house in Saraswathipuram, with Prakash my best friend in the

neighbourhood and his little sister and my own in tow. The conversationists,

who visited and mostly sat in the grill windowed veranda, formed the backdrop.

Their voices in the midst of a heated discussion rose and faded as we darted in

and out of the veranda.

They were from diverse

backgrounds – political activists that included both Lohiaites and communists,

young Kannada writers and critics, budding theatre artists and, I remember as

this had caused great excitement, a young and upcoming magician who had brought

with him a entire box of sleight-of-hand tricks as a present for me. All of

them came to share their experiences, often for advice about their work and

sometimes because they continued to be mesmerized by a speech he might have given

at a college, or bank employees association (I remember the magician was a bank

employee about to quit his job to follow his true calling). Once, the ‘math

wizard’, Shakuntala Devi, showed up at our doorstep, Samskara in hand, wanting

him to autograph it while she narrated her life story!

It could have been that appa was somewhere

fulfilling my appaiah’s (his father) desire to see him take up

mathematics as a career choice, for he would readily offer to engage himself in

our math homework. He had an uncanny ability for solving algebra problems, or

proving geometry theorems. Anuradha didn’t seem to need much help at school,

but I did, especially in math. We had a wonderful math teacher in school but he

mostly spent the class hour talking about atheism and Russell. So, all the real

problem solving was left to appa, who would first ask me for some basic

information by way of brushing up and then sit down and neatly derive something

or provide the proof of a difficult rider in geometry. Anu and I had a nickname

for him when he professed his math or analytical abilities. We called him

Bertek when he put on the hat of a mathematician or scientist. So we’d tease

Bertek about his ‘scientific interests’ to pull him down, especially when he

gloated about solving a difficult problem that had bothered us for long.

But growing up wasn’t

all just to do with math and science. Appa had a passion for nonsense rhymes

and poetry and encouraged us to make up long strings of interesting sounding

words that made no sense. A photograph in an old magazine with two characters

in a pool had caught my fancy making me christen them ‘fussy fuzzle fut and

mooshi moot’. Appa and I delighted in looking at this photo from time to time,

and each time these names would come into my head. Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass were our big time favourites and he used to read out different

passages from these works to us. One way that appa and Anu would get back at me

was by inventing new languages with some simple rules and conversing rapidly

with each other. One such was sa-bhashe, where they’d prefix a sa to the normal Kannada sounds, reeling off sentences in this manner

till I became really irritated at failing to decipher as quickly as they spoke

by taking off the sa from the syllables.

The seventies saw appa arguing his way through

Maoism and China with the leftist friends who came home. When I think back I

can’t recall when these political ideas and discussion seeped into my head and

got me interested in them, but I recall that I often talked to my classmates at

school about some of the things I heard at home during appa’s conversations

with these visitors. He educated both his brothers through their college and

they stayed with us in turn. Anil, the younger one studying MBBS, had a large

circle of Marxist friends who were regular visitors. One of Anil’s classmates,

Lakshminarayan, kept us abreast with the latest events in China. The Cultural

Revolution was a topic of much discussion. It all seemed quite exciting. What I

picked up from the animated discussions, jokes and loud banter, was a liberal

sprinkling of terms like ‘petite bourgeois’, ‘adventurist’, ‘lumpen

proletariat’, ‘comprador capitalist’ and so on. Appa’s disillusionment with

China’s experiments seemed evident from his later remarks about the irony

behind Mao’s Long March that eventually led the Chinese to Coca Cola! This

disillusionment was to slip further into a deep sense of anguish after the

Tiananmen Square incident he happened to witness on a visit to China.

The mid-seventies had a very special effect on me

and appa. I had found many new interests by then, many of them having their

origin in a bag of musical goodies consisting of cassettes and vinyl records

that appa’s hippie and campus radical friends had helped select for him during

his first long stay abroad as a visiting writer and fellow at the well known

Iowa Writers’ Programme in the US. These records and music, ranging from Miles

Davis and John Coltrane to the seventies bands such as The Band, Bob Dylan, and

to classical music (Rachmaninoff, Dvorak), transformed into a continuous

musical extravaganza in our little study. To this was added M.D. Ramanathan’s

deep tonality of Carnatic renditions and a record of Kumar Gandharva gifted by

A.K. Ramanujan on one of his annual visits from Chicago (his visits were

received by the whole family with great rejoice). The Allahabad High Courts’

indictment of Indira Gandhi was out and her arrest seemed to appa as if they

were ‘hanging her for a parking offence’, although her authoritarian politics

had deeply disturbed him.

The news of the

Emergency came amidst his activity with other socialists and student political

leaders in the university. Although it was believed that Karnataka’s chief

minister at the time, Devaraj Urs, was being somewhat kinder to the opposition,

many politicians in Karnataka, as elsewhere, went behind bars under the

infamous MISA (Maintenance of Internal Security Act). Many of them were appa’s

friends. He threw himself into many underground type of activities. Much of the

discussion with sometimes mysterious looking visitors to the house, amidst amma’s worry that appa was entangling himself in ‘quite unnecessary

things’, would be in hushed tones, while the music continuously played in the

background in our little study. As a thirteen year old, my own interest in

politics and the events in Karnataka were kindled by these goings on.

An invitation to appa

around that time from the Institute of Advanced Studies in Shimla was an

opportunity to take the entire family on our first big tour to the North. In

Delhi, we stayed – both en route to Shimla and on the way back – with appa’s

close friend, the Hindi poet Kamlesh. I remember the days spent in his house

vividly. Kamlesh appeared preoccupied with many other matters amidst the

generous hospitality and late evening dinner parties he arranged in honour of

his good friend. After all the guests had left he would talk to appa about

someone’s visits or about some of the socialist friends who had been arrested.

On some nights, on our way back from the local sight seeing tours, he could be

seen near the house on the road waiting for ‘someone’.

One afternoon a visitor, who looked like a sadhu,

arrived at Kamlesh’s house. He asked appa if he recognized him and upon drawing

a blank remarked, ‘Good that you don’t recognize me’. I ran inside excitedly

and told amma that I recognized George Fernandes even in disguise while appa

had not! After he left, I realized that the Mark Twain book I was reading on

that trip had vanished! George Fernandes had to spend many long days in rooms

in churches or places where quiet supporters of his fight against the Emergency

accommodated him, and appa tried to console me that my book was being put to

some good reading. We didn’t realize till much later, when Kamlesh, along with

C.G.K. Reddy, George Fernandes and others was charged with conspiring to

disrupt the peace through violence (what became known as the Baroda Dynamite

Conspiracy), that all the gelatin sticks had been stocked in the house we had stayed

in.

In Mysore, appa continued to be actively involved

with a mix of people, all arraigned against the Emergency – leftists, Jana

Sanghis and also RSS activists, then in hiding or with pseudonyms. The RSS

network was responsible for passing on messages across the country and appa was

genuinely impressed by the discipline and commitment they had shown in this

enterprise.

We used to have a

‘Saliyan’, a dark complexioned person, visit our home at all odd hours. He was

the only visitor who would also talk to me in between his conversations with

appa. Soon after the Emergency was lifted and the RSS shakhas started to be held in the open, Saliyan gently suggested that I

visit one of their shakhas. I went one day and stood on the side watching. I

was quite drawn to the games they played and the exercise and drills. So I went

and asked appa if I could join. He said he would have no problem but what about

my friend Alamdaar who used to come home to play with me every evening? ‘Could

he join as well?’ I asked Saliyan. He only said that Alamdaar may not join even

if I asked him to come along. I never went to the shakha nor did Saliyan try

persuading me again.

Appa was not an

authoritarian at home. He never forced me or Anu to pursue any particular

career. He lived a life steeped in a universe of ideas, ideas that often

complemented each other, or came into conflict. Being a teacher was for him a

way to pursue these ideas. We were brought up in a milieu wherein worldly

pursuits were looked down upon and lucrative career choices regarded with

disdain. One lived a worthwhile life only through living a life of the mind! So

my decision to pursue science was welcomed, for appa saw the life of an

academic and teacher as worthwhile. When Anu, who was studying medicine, moved

away from her Carnatic music practice, he was saddened that she was giving up

the pursuit of a great art form.

Appa continuously fought the Brahminism that he

saw around him and opposed other kinds of casteism that he encountered in

others. Although it was love that drew him to my mother when they married, the

fact that she was Christian, I can’t help feeling, had a strong role to play in

both his rejection of his own encumbrances attached to his upbringing as a

Brahmin as well as his attraction later on to asserting his caste identity at a

personal level through rituals that he started to observe. In the habits of our

quotidian life, wherein mother did not practice her religion actively, nor went

to church, nor tried to steer her children towards the Christian faith, but

left out all religious ritual and served non-vegetarian food on the table, we

found him, much more in his later years, asserting his vegetarian Brahmin

identity by refusing to eat the non-vegetarian food served.

Mother’s family is

Protestant Kannada Christian, and my grandparents from her side were devout

church goers. My thaata (grandfather), a man of great self-contentment

sat quietly, often deeply engrossed in painting and sketching wildlife. He

would be found sometimes upon visits to our Mysore home, notebook and pen in

hand, translating the Bible into Kannada. My grandparents’ view of their

Brahmin son-in-law, initially with a little trepidation about the possible

eroding of Christian values in our household, later transformed into adulation

and pride as they watched his growing fame in the Kannada literary and

political worlds. His long discourses about aspects of the Bible and gentle

admonishments to other younger members of my mother’s family about not studying

the Bible with enough care, helped matters further in earning him the favourite

son-in-law spot.

My first big move away from the comfort zone of

my home and the warmth and security of my Mysorean existence in moving to

Kanpur was the point in time when I felt ‘grown up’. Appa continued to be a

large presence in my life even then in advising me on all kinds of matters

related to love – I had taken quite seriously a college love affair that then

seemed to be the cause of my reluctance to study in a place other than Mysore –

growing up away from home, and the pursuit of knowledge. Appa, upon seeing me

in a state of agony about this affair, quietly went one day to talk to the

girl’s parents and her brothers. He returned grim faced and looked rather upset

at being lectured about life and decisions to be made by her still

wet-behind-the-ears brothers. He gently revealed this to me, and I could see he

didn’t think much of them or their advice! By his tone, I could make out that

he was saying that he had tried, but that I was free to follow my heart. I did

move out of Mysore and also away from the affairs of the heart. He continued

being this presence even as I left to study in the US, and in bringing close to

me many friends who are writers and artists and who I met because of him, while

studying there. Appa became guru to many of them.

I was thirty when I

returned to Bangalore, with much travel and years behind, but none the wiser

from these experiences, when I re-encountered appa. He had grown enormously in

stature. Our exchanges as adults marked a different phase in my life, but that

narrative I will save for another time.

Inheritances

SHARMISTHA MOHANTY

IN the flat, snow

covered plains of the American Midwest, U.R. Ananthamurthy came to us – a small

group of Indian students – bearing fragments of our own inheritance. With his

singular vision and energy, he helped us to begin to see some of the diverse

things that had made us. It was a transformation for us – students of writing at

the Iowa Writers Workshop, students of filmmaking and the sciences. He brought

out magical books from his bag. TheArdhakathanika, the first ever

autobiography written in India, in the seventeenth century, the just written The Intimate Enemy by Ashis Nandy, and Simone Weil’s Waiting for God. The force of that encounter over many months

would leave its mark on all our lives. As would the paradox it contained, the

fact that an encounter such as this was perhaps more powerful in that far away

soil of Iowa.

The most searing thing

about Ananthamurthy’s novels and stories is their activeness. The best of them

do not reflect people and transformations, nor recreate or mirror them. What

they do is face and confront. They do not recollect or recount, the tale unfolds

as an intensely alive presence. Ananthamurthy was no doubt a public

intellectual, a thinker, but it was his writing that I believe formed the core

from which everything else emerged. It is in his fiction that he explored his

ideas and often found his own vision. ‘(In Bharathipura)

I give full scope to my ideological position. But the novel questions it,

reflects on it, interrogates it, and turns the other way. That should happen in

the process of writing. And I magically get it sometimes.’

One of the things at the heart of his gift as a

writer was his ability to locate and understand ambiguity, as something not

merely to be lived with, but to live by, especially in the context of India. In

a long short story, ‘Clip Joint’, the narrator is in England for an extended

period of time as a student. He has a close friendship with Stewart, an

Englishman. He says to himself, ‘...the intensity of a life that grows in the

stench of mud and urine – an intensity that precedes all mysticism. ...But here

in this clean and well-ordered land of Stewart’s, only genteel humanists but no

mystics are born.’

Ananthamurthy is best

known for his first book, Samskara. This is clearly a more allegorical work. Where

Samskara has dichotomies, Bharathipura has dilemmas; where Samskara has a

decaying corpse, Bharathipura has death and dead lives. Very rarely does a

novel have a narrator who acts with conviction, and is profoundly uncertain at

the same time, as Jagannath is in Bharathipura. The moment when Jagannath urges

the Dalits to touch thesaligrama is perhaps one of the most moving passages in Indian literature.

‘All that he wanted to

say stuck in his throat: "This is primary matter, touch it; I hold my life

in my hand as I offer this to you, touch it; touch the deepest part of my innermost

being; this is the propitious moment of evening worship, touch it. In vain is

the eternal flame burning there in the puja room. The people standing behind me

are pulling me towards them, reminding me of countless obligations. What are

you waiting for? What am I offering to you? This is the way it is: only because

I offer this to you as a mere stone, it’s becoming the saligrama. If you touch what I offer you, it’ll become a

mere stone to all of them. My anguish is becoming the saligrama; because I offer it to you and because you touch it and because

they see you touching it, let the stone become the saligrama and let the saligrama become a stone, even as the evening deepens.

Pilla, you’re not scared of the wild hog and even the tiger. Come on, touch it.

After this, you’ll have just one more step to take, enter the temple. Then,

centuries of belief will be turned upside down. Now, come on, touch this. Touch

it now. See how easy it is. Touch it".’

A gesture can hardly be

more ambiguous than it is here, a devastating ambiguity which holds both hope

and hopelessness. Jagannath’s consciousness oscillates between the two. This is

done in and through language, with a writer’s gift. He knows to say this in one

long paragraph, building it up sentence upon sentence that communicates the

intensity of Jagannath’s desire for change, sentences long and sinuous, broken

sometimes by the deepest questions, and the repetition of ‘touch it’ – all this

creates the entire world of caste and tradition and the centuries that stand

behind it, in one moment, together. So Ananthamurthy’s craft serves his gaze

and produces an emotion and insight that only literature allows.

Things are as active and alive in the masterful

short story, ‘Suryana Kudure’ (The Stallion of the Sun). Here the

encounter is between a village man, more or less a village idiot and an

educated man of the village who studied abroad and has returned to live in a

city. Here, the dialogue continues between the old and the new, tradition and

modernity, belief and doubt. At the end of the story, as in so much of

Ananthamurthy’s work, the ambiguity remains unresolved, that being the story’s

deepest truth, one that we must live by. The story leaves behind a strong

disturbance in the mind, a desire to choose between the two ways of being, and

the inability to do so, because an empathy develops for both. However much we

travel, upon our return there will be another way of living that confronts us

with its own certainties, making ours waver.

Octavio Paz, in his In Light of India,

says: ‘Hindu civilization is the theatre of a dialogue between One and Zero,

being and emptiness, Yes and No… The fast negates the feast, the silence of the

mystic negates the words of the poet and the philosopher.’ This was the arena

in which Ananthamurthy’s writing existed. Where Paz, as an outsider, sharply

saw the opposites, Ananthamurthy went much further to the place where yes could

become no, the saligram and the stone constantly exchanging places.

I remember a large photograph of Ramakrishna with

his eyes closed, turning in a kind of trance, in Ananthamurthy’s study in

Bangalore. In the same study was another photograph, Tagore and Gandhi together

in Santiniketan.

He spoke often of the

three hungers of the soul (after Simone Weil) that animated the previous

century in our country – the hunger for modernity, equality, and spirituality.

All over the country writers like him were inspired by these urges, he said.

‘But equality as hunger of the soul is not easily satiated unless it gets

coupled, as it does in some great sages of all times – with the other hunger,

the spiritual hunger. Both these hungers have their origin in the feeling that

all forms of life are sacred and our routine quotidian existence in the temporal

world is boring unless it glows with a transcendental meaning.’

Possibly, his fiction could have pushed further

in this direction. But the realist novel that he chose as a form would always

privilege the human drama, and push everything else to the background. If all

living beings and things were indeed sacred then literature would need a form

where the human and the non-human had a certain equality. It is surprising that literature in our context

has not taken on and made greater use of the overwhelming tradition that we are

still privileged to have – of myth, legend, magic, epic and so much that is

outside the framework of the rational. He once told me that Marquez would

remain limited because beyond a point ‘you cannot exceed excess’. There may well

be a grain of truth in that, but I felt he ignored the fact that the same could

be said of the realist novel which has lost its energy over time. It can as

easily be said that too much reality ultimately will be unable to express the

very essence of that reality. I think he possessed the gift of creating a work

which was not reducible to any kind of sociology or politics, but which

included both and much else besides. Perhaps the man of action and the man of

reflection were competing with each other in his work.

One issue he never

changed his mind about was Indian writing in English. Our arguments about this

continued over the years. He felt that Indian writing in English could never be

‘authentic’, that English did not have a ‘backyard’ as the Indian languages

did, that it could never manifest our most intimate feelings. These views have

drawn much criticism over the years. As part of a generation and perhaps a

class produced by English education, I could not agree. We are in some sense

made by history, and how are we to change our situation? Ananthamurthy used to

laugh and call us – people like his son Sharath and myself – ‘the petrol

generation’, products of movement, with spouses from other communities.

Over the years I have thought more about his views

on this. Possibly because I am aware of the radiance of his mind that I know

his words did not emanate from prejudice but from a deeper part of himself.

Today, I do see that Indian writing in English, especially fiction, lacks a

certain depth, and definitely a certain rooted-ness, unable to penetrate our

diversities and our paradoxes. It is difficult, I feel now, to write in a

language one barely hears on the street or in one’s daily interactions. There

is no access to the different registers a language always has. As a result, the

writing in Indian English can seem postured, its rhythms unmusical, its

attitude formal. The only way that English can be used maybe in a deeply poetic

mode where one speaks not so much to others but almost to one’s own soul.

One of the inheritances

Ananthamurthy has left behind for me is living with the ambiguity that he was

such a master at locating. As I continue to be a writer in English, I live with

the questions he raised, with a kind of acceptance and interrogation of my own

ambiguous situation. Ananthamurthy was a rare mind, and I continue to wonder

whether such a mind could have been produced without rooted-ness in a soil and

a community together with a going away to give it perspective. I will mourn his

passing, even as I celebrate the luminosity of his vision.

* Sharmistha Mohanty is

a fiction writer. She first met Ananthamurthy while studying at the Iowa

Writers Workshop, and he remained a teacher and a friend for thirty years.

Mohanty is the author of three works of fiction, Book One, New Life, and Five Movements in Praise.

Memories

VIVEK SHANBHAG

WHEN relatives leave

after a short visit, it is customary for them to give some money to the

children of the house. To immediately hand it over to ammais also customary. Once, my aunt, who was returning to Mumbai

after spending a few days with us, gave me ten rupees. ‘Buy something,’ she

said. Had this episode transpired at home, I would have had to hand over the

money to amma. I had gone to drop her off, and just before the bus moved out of

the stand, she had, in a hurry, stretched her hand out of the window and thrust

that folded note into my palm. I went straight to a bookshop without the

faintest idea of what book to buy.

As I stood there

browsing through the glass shelf, I saw Bharathipura,

its green title page covered with half sentences. The words left me shaken.

Till then I had neither come across such language nor such thoughts. I was

mesmerized. I have not yet forgotten the lines that I read that day at the

shop: ‘…because of Manjunatha our lifestyle has stagnated. We are rotting. Once

we destroy Manjunatha we’ll have to become responsible for our lives… What’s

important right now is to prepare the Holeyaru for it. We’ll have to make them

take their first step in history. Their first step across the threshold of the

temple may change the reality of centuries...’ I handed over my ten rupees,

bought the book and went straight home, not getting up till I had finished it.

I was 15 years old at the time.

The kind of disturbance

that Bharatipura created in me cannot be easily described. The way language had

been deployed was itself new to me. I myself went through the turmoil of the

protagonist.

After Bharatipura, I

turned towards a different kind of reading. This was a major turn in my life.

The magic of Ananthamurthy’s writings came from the fact that he could

articulate complex issues with great clarity and connect them to everyday

experiences. Using this magic, he reached every nook and corner of the reader’s

mind to transform an idea into an experience. I feel that it was this talent of

Ananthamurthy that angered fundamentalists. Ananthamurthy’s writings and the

metaphors he used obviously disturbed them deeply. The fundamentalist brigade

must have been astounded by the lucidity of his thoughts; I clearly recall the

restlessness I went through after reading Bharatipura.

Two years after I read Bharatipura, I got a

chance to meet URA. At the time I was studying in a small town called Ankola. I

was thrilled by the fact that a major writer like Ananthamurthy was willing to

come for the annual day of the Shetageri village high school. The famous critic

G.H. Nayak was responsible for bringing Ananthamurthy, and when I learnt that

Nayak was in Ankola, I went looking for him. Though I was a complete stranger,

Nayak spoke affectionately. He told me that Ananthamurthy was arriving by the

Bangalore bus the following morning and invited me to join them for breakfast

at his house.

I had been asked to come

at 7 am, but I was so restless that I reached the bus stand much earlier. I

had, since Bharathipura, read all of Ananthmurthy’s books twice over.

Meanwhile, my very first short story was awarded a prize. Therefore, I

entertained few doubts about my importance as a writer! Indulging myself in

such thoughts, I waited eagerly to see Ananthamurthy. There was only one bus

that came from Bangalore. It had yet to arrive. G.H. Nayak and the principal of

the Shetgeri High School were already there. We stood under a tree, chatting as

we waited for the bus.

That day the bus came

late, around 8 am. I spotted him sitting by the window, wearing a gray and

yellow sweater. Nayak went ahead and received him. And I was right behind.

Taking off his sweater, the first words he uttered are still etched in my mind.

‘There was a huge downpour in Bangalore. It was very difficult to find an auto

to reach the bus stand.’ Nayak introduced me to him. At around 9 am, I went to

their house for breakfast. I sat intently listening to their conversation. But

in a few minutes, I was disappointed. Ananthamurthy spoke about everything in

the world except literature. Farmer’s revolutions, the schools and colleges

that had been set up by Dinakar Desai, social revolution and much else – he

seemed more concerned about contemporary politics.

Now, as a result of the

many years of my close relationship with him, this aspect of his doesn’t

surprise me. It was inherent to his nature. Till his illness made it difficult

for him to travel, he loved going to schools and colleges in small towns. He

was extremely interested in what youngster’s wrote. Till his last days he never

lost the enthusiasm to read new writing and would contact the authors. He wrote

letters, and told everyone about it. Ananthamurthy could see the strengths and

limitations in a piece of writing and was honest in offering his criticism –

this was valued by new writers on the block.

In the days when I didn’t know him all that well,

he had written a letter to me after reading one of my stories; it remains a

cherished moment, and this is true of many Kannada writers. He would create an

informal atmosphere making it possible for anyone to approach him, to hand over

their manuscripts and ask him for an opinion. This kind of an interactive

environment, especially for younger writers, seems now a distant memory. If

someone were to put down some features of the Ananthamurthy era, this certainly

would be an important one.

Since he was deeply

interested in the world around him, no one that he came in contact with was

allowed to slip away. It could have been the carpenter, the farm labourer

Ramaiah, a computer engineer, or even the big and famous – he would talk to

them with great interest, without being judgmental. It was this interest that

made him such an active participant at the three-day science seminar at

Heggodu. He raised key ethical questions, which were seriously discussed at the

gathering.

Talking about questions,

I remember that he never treated even the most ordinary question with

disinterest. He genuinely believed that it was inner provocation that prompted

a person to ask a question and so helped them to articulate it with greater

clarity – a lesson in lucidity of thought, that also gave the person asking the

question a boost in self-confidence. But, if the question was to merely test

his integrity, he became immensely angry.

To share and to build

together was an integral part of his personality and thought process. People

came to meet him all through the day; he never rejected anyone. His thoughts,

his writing plans, political responses were discussed with several friends even

before they came to occupy public space. Irrespective of a person’s age and

background, he would engage in a meaningful conversation with them and, most

importantly, take their feedback seriously. If at all he could foresee a reader

response and its repercussions, this was probably the reason. I feel his

interactions with people of diverse backgrounds influenced the structure of his

narratives, the manner in which his thoughts developed, and his ability to yoke

together dissimilar elements.

His participation with the larger community had a

bearing on his writing process. Everything was kept ready somewhere, and it was

as if he was merely putting them on paper – he wrote his essays in one sitting.

Of course, he made minor corrections here and there, but there wasn’t much of a

difference between the first and final draft. Because of this ability, he could

dictate when unable to spend long hours before the computer. Another Kannada

writer who had this ability was Shivaram Karanth. Such an exercise is

impossible unless one has total clarity of thought.

This was true of his

speeches too. I never saw him make elaborate notes for any of his lectures. His

talks, like his writing, were also an outcome of his imaginative fabric. The

immediacy in his speeches came from here, I suppose. During the proceedings, he

would put down a few words on the back of an envelope, or make some random

jottings on the last page of a notepad – this was his preparation. He would

start talking and thoughts would fall in place. I feel he loved to make

speeches because of the creative pleasure he derived from the process, possibly

also the reason why they were so tentative and charming. He spoke with a sense

of wonderment as these creative impulses worked within him, and he had the

ability to transfer it to his audience as well. ‘It occurred to me at that

moment, just as I was speaking,’ was something I have heard him say so many

times.

I watched him closely when he was translating Tao The Ching. For nearly a month and a half in Mysore, he worked for 10-12

hours a day. Night and day he would think of only this, making a minimum of

four versions for each poem. It was not merely a translation, it was an excuse

for a search within. If you read his Foreword to Tao The Ching, the point I am

making will become clear. He could also create the solitude required for his

writing wherever he was. It didn’t need a specific place or time. Once having

started, the writing would flow continuously, the buzzing world around him

proved no impediment. That is how, even when he was travelling continuously and

actively engaged in public life, he could immerse himself in writing as well.

His views on contemporary politics, however, left

me nervous, almost as if I did not want to believe that it could happen. I had

a reason to feel so. In 1996, Ramakrishna Hegde and Deve Gowda were both part

of the Janata Dal during the assembly elections in Karnataka. On the day of

counting Ananthamurthy was staying with us. At seven in the morning, Deve Gowda

came to our house with a friend, who now occupies a key position in the

Congress. Deve Gowda’s confidence and political experience was so sound that he

could accurately predict the number of seats a party would win. When the

results were declared, there was a difference of a mere three seats.

Despite it being

counting day, there was a reason for Deve Gowda to spend those three hours at

our house. He wanted Ananthamurthy to convince Hegde not to come in the way of

his becoming the chief minister. I have a hunch that he left only after

extracting a promise from Ananthamurthy. After he left, Ananthamurthy wrote a

letter to Hegde. In it, he discussed the entire political scenario of the

country and also the forthcoming Lok Sabha elections. No party may win a

majority, regional parties may become major players and would possibly come to

power at the Centre, his letter predicted. And in such a scenario, he advised

Hegde to move to national politics and let Deve Gowda take on the

responsibility of the state. At that point this seemed impossible. I don’t know

what Hegde took into account, what kinds of alliances took place, but Deve

Gowda did become the chief minister. The rest is history and every-one knows

how Deve Gowda expelled Hegde from the party! In retrospect, this letter

appears like a prophecy to me. Hence, the intensity of his emotions and views

on contemporary politics and Narendra Modi made me nervous.

Our last conversation

was when he was in hospital. His book Hindutva and Hind Swaraj was ready for publishing. It was a book born from deep thought. He

had revised it several times. The power of its language, the fiction-like

narrative, and the progression of ideas that seem like incidents from a novel,

will leave a lasting impact on the reader’s consciousness. That day, in the

hospital, he spoke about the thoughts of Richard Rorty. ‘It could be history or

sociology; if there is no faith that man can change, then all the work that’s

happening in these fields is useless,’ he said. A little later he spoke about

Shivaram Karanth, and recalling my comment, added, ‘It is time for us to reread

Karanth again.’ Both these responses were typical of his nature.

Like everyone else who came into contact with

him, I too was mesmerized by his persona, and experienced great happiness in

his company. As a writer it was also inevitable that I would seek to break free

from that influence. All these thoughts are a recollection of those moments of

pleasure and anguish.

In these 25 years since

I have been a part of his family and closely interacted with him in those

thousands of meetings, I never returned empty-handed. He always had something

new to share. There was always some new idea, new thought or a new book to talk

about. This was true till the last meeting. It is indeed rare that someone who

you are close to remains constantly new, even after all these years.

* Translated from

Kannada by Deepa Ganesh.

Transcending imaginary divisions

SRIKANTH SASTRY

THE first time I saw and

heard Ananthamurthy was on a vacation home to Bangalore from Boston where I was

pursuing a PhD in Physics at the time. In the long years away from home, I had

begun to dabble with writing in Kannada as a way of keeping alive a meaningful

connection with my mother tongue, and to catch up on Kannada literature that I

had not paid much attention to when I lived in Bangalore. This engagement with

writing in Kannada had become quite a serious preoccupation in those days, and

all things literary took priority over other engagements during the visit.

When M.S. Murthy, an

artist in Bangalore who I had recently met, told me of a public discussion at

Ravindra Kalakshetra with Ananthamurthy who was visiting town (he was vice

chancellor of Mahatma Gandhi University in Kerala in those days), I eagerly

tagged along. I don’t recall much of what was actually said, but do remember

that it was an extended dialogue, with Ananthamurthy engaging his interlocutors

with obvious relish and earnestness. It was an appealing vignette of an

engagement that I was an outsider to, but for quite some time it would remain

an isolated cultural experience, given my intellectual and geographic distance.

It was a pleasant

coincidence that drew me back into contact with Ananthamurthy after returning

to India. Owing to a shared profession and common friends, I met Sharath, his

son, and we got to know each other well. Soon thereafter, there were frequent

occasions for me to meet Ananthamurthy, and to have conversations that covered

a vast cultural universe, which became, over time, a beacon for how I view

myself, my work, society and culture.

What struck me the most

about Ananthamurthy was his serious and incessant engagement with ideas and the

world around him. This was a constant, enduring meditation of a man who never

ceased to strive to comprehend, to synthesize, and to formulate a position on

all that came his way, and was ever eager to share, to question, and be

questioned. The process itself, rather than any purpose that lay beyond, was

the ultimate, unremitting yajna, which was at the same time effortless as a

natural part of his being, but with a fierceness of focus that could easily

tire the less energetic ones around him.

The broad canvass of

Ananthamurthy’s contemplations were his deep concerns about the directions of

modern civilization, the fate of dominated cultures, ways of living and

knowing, and what notions of development held in store for them. Many concerns

revolved around globalization, cultural and economic, and its relation to

civilizational trends.

A particular strand of his concerns revolved

around the role of science in determining the nature of contemporary society.

As a practicing scientist, I often found myself being a sounding board, and

sometimes a punching bag, to his engagement with this theme. Ananthamurthy’s

principal concerns revolved around what may be called the epistemic hegemony of

science, the implications of scientific knowledge, past and present, on human

affairs, and the nature of the public participation of scientists in these matters.

A common experience when

I visited him at home would be for him to tell me about the latest matter that

he was engaged in a public discussion about. At some point during this

discussion, he would interject a comment – ‘and no scientist is talking about

this’. He felt that scientists should actively participate in public discussion

on matters of societal importance, and was generally disappointed at the level

of such participation. This point is an interesting one to ponder over.