Economic & Political Weekly EPW may 24, 2014 vol xlix no 21

Narendra Modi has won a massive victory but his ascendance does not portend positive change.

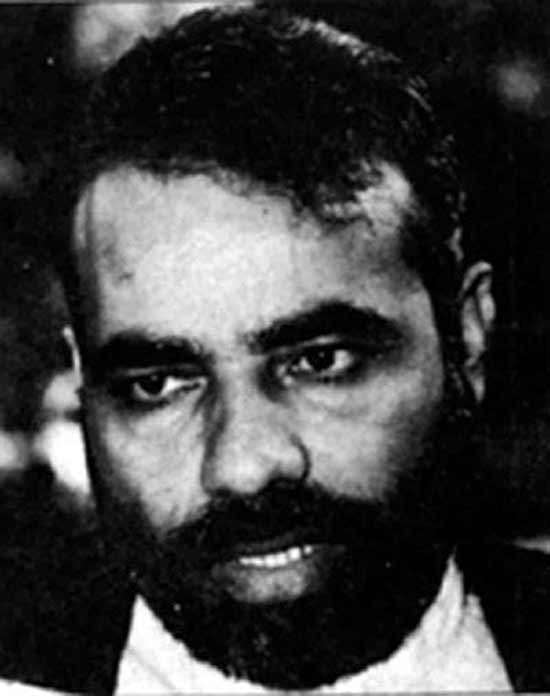

In the months leading up to Elections 2014, the media, in its anxiety to project Narendra Modi as the next prime minister, frequently described the 16th Lok Sabha elections as the most important ever. Prone to its usual exaggeration the media forgot that in terms of outcomes there have been bigger landmarks in the past – 1967 when the two-decade-old Congress monopoly was first weakened, 1977 when Indira Gandhi was voted out after the Emergency and 1998 when the first ever Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led coalition came to power. Elections 2014 have indeed turned out to be a landmark, but not because Narendra Modi has led the BJP and the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) to a huge win that has led to a single party enjoying majority in Parliament for the first time in 30 years.

This was an election that the ultimate victor had set out planning for years ago. It was an election for which, beginning in 2012, international public relation agencies were hired to build a persona for Narendra Modi, with a positive spin (“development”, “the Gujarat model”, “governance”, “decisive”, etc) covering up the negatives (centralisation of power, authoritarian tendencies, and being the chief minister of a state when some of the country’s worst communal riots took place). It was an election, which, because of the spin and the promise of a business-friendly government, most of the corporates in the country ended up endorsing one candidate. It was an election that consequently saw an unprecedented amount of funds flow to one party, which, according to one independent estimate, ended up spending more than Rs 5,000 crore on just advertising, only a little less than the $986 million that United States President Barack Obama spent on his 2012 presidential campaign in a country where the per capita income is more than 30 times that in India. It was an election where the media months ago bought into the message of the well-funded party and had no compunction about either refusing to interrogate the claims of past achievements and future promises of its prime minister aspirant, or about promoting a collective amnesia about Gujarat 2002. It was an election where the vast resources that were collected were used to mobilise, motivate and monitor the victor’s campaign down to the last detail, with no small help from the organiser par excellence – the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). It was an election that can, with some justifiable exaggeration, be called the biggest corporate heist in history. When Indian capital embraced its natural ally, a right-wing party that promised to be pro-business.

This is not to gloss over the sins of commission and omission of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government – in particular of the Congress Party – that have helped the BJP march to victory. A party that headed a venal government and now more than ever before has been converted into family property stood little chance against the BJP’s military-like campaign. The UPA government’s dismal record on inflation control and employment generation more than overshadowed its limited achievements by way of some rights, some improvement in human development and some social security legislation, which in any case were all drowned by the promises of the Narendra Modi machine.

The Modi campaign was organised around the message of “development”, all gloss and empty of content, and aimed at taking full advantage of voter fatigue with the UPA government and anger against its corruption. Yet, it was not always possible to keep the mask in place. It was not the vitriol that the prime minister aspirant (now prime minister elect) used during the campaign that should worry us but the messages he occasionally sent to the Hindu vote bloc. Talk about sending back migrants from Bangladesh, about who benefits from “pink” (that is beef) exports and half-hearted criticism of statements such as those opposed to Modi should go to Pakistan were clear signals that the prime minister aspirant had not “moderated”. It is also instructive that not once in his campaign did Modi reach out to the minorities to assuage any misgivings they may have had about him as a prime minister. There is therefore good reason to worry about the future of a pluralistic India under a Modi government that will enjoy a commanding majority in Parliament but without a single Muslim member of Parliament in its ranks.

If a prime minister, who as chief minister of Gujarat oversaw no more than a middling improvement in human development indicators, disappoints his voter base on “development”, the danger of Hindutva raising its ugly head is ever present. Modi is an RSS pracharak but he has not always done his organisation’s bidding. However, there is a renewed closeness between the two and even before the results were announced, senior officials of the RSS were already speaking about the Ram temple and the Uniform Civil Code.

As the Modi campaign gathered momentum there were signs that the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate was becoming “acceptable” to a number of important political agents as well as intellectuals. Those who should know better claimed that New Delhi will “tame” the Narendra Modi of Gandhinagar. The argument is that as prime minister of a vast country, Modi will be unable, even if he tried, to undermine democracy because institutions such as the Supreme Court, the Election Commission and the Comptroller and Auditor General have demonstrated their independence from the Executive. There is little to defend in this head-in-the-sand view which is worrying not so muchfor the resignation it conveys as for its unwillingness to fight a dangerous force in Indian democracy.

If one thing is apparent in the Republic, it is that 60 years after it was formed, the institutions of democracy at many levels remain fragile and open to capture. We see how from panchayati raj, the lower judiciary and the Executive at the district upwards, right up to New Delhi, institutions can be subverted and are vulnerable to capture by forces like the RSS that work with a vision and mission. We also see how even autonomous institutions of democracy can be quick to abandon their independence when they come up against a powerful and organised force. Why, our apparently independent media showed this very trait once it smelt that Modi was on the ascendance. The higher judiciary is not very different. While its independence and power in recent years ran alongside a weak Executive, a strong Executive (as during the Indira Gandhi regime of 1971-76) has shown that it can make even the Supreme Court bend to its will.

Perhaps of greatest concern is that we now have the Sangh Parivar being presented with a clear opportunity to reshape the Indian polity in line with its decades-old Hindutva project. The majority the BJP will enjoy on its own in Parliament and the decimation of the opposition must therefore be viewed with apprehension, rather than as a positive development. In the NDA government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the BJP was, in comparison, hobbled by allies and a small majority in Parliament and could go only so far and no further with Hindutva.

Other than in states where the regional parties showed their strength (Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Odisha and Andhra Pradesh), the election was about Narendra Modi (his promises versus his divisive personality) who, in turn, easily turned it into a referendum on the incompetence of Congress Vice-President Rahul Gandhi. The future of India did revolve around the suitability of a divisive and polarising personality to head the Government of India but it should have also revolved around the concrete agenda that political parties were offering the electorate. And here conspicuous with their absence, perhaps more than in the past, were discussions and debates about what the main political parties could place before the people of India. What we witnessed instead was a campaign that mobilised an electorate thirsting for change and that was run in an aggressive fashion without much concern and respect for all communities and classes.

If there is a message from Elections 2014 it is that India has been changing. It is becoming a society where those with a voice are becoming less tolerant, less compassionate and more aggressive towards those without a voice. This is just the atmosphere for an aggressive mix of religion and nationalism to find expression. It will therefore be a huge challenge for individuals, groups and parties concerned about democratic and human rights – who have been marginalised in Elections 2014 – to monitor and keep a check on the BJP/NDA government so that a pluralistic India can look forward to a peaceful future in which the well-being of all is at the centre. The “new era” that the BJP has declared is not something to be viewed with optimism, it should perhaps be viewed with scepticism and apprehension.